Hi all! I’ve done a little writing about art that culminates in my upcoming book’s cover reveal. Fair warning, some of this art details violence to women. Well, one woman in particular. And there’s a lot of boob talk.

My Book Is Named After a Saint

Agatha lived in Catania, Sicily, at the foot of Mt. Etna, from 231-251 AD. She was noble born and a “virgin martyr.” Pursued and tortured by a Roman official, Quintianus, Agatha was sent to a brothel to “overcome her resistance” when she refused his advances.

Later, among other tortures like the rack, Agatha’s breasts were torn from her body, and she was sent to prison where Quintianus forbade medical care. According to legend, Saint Peter appeared to her and healed her wounds. Quintianus next ordered her raked over hot coals naked, but during that ordeal an earthquake shook the city. Agatha died soon after in prison.

She was never quiet, always defiant, which enraged her tormentor. In my book, she is this Agatha.

Agatha is the patron saint of breast cancer patients, bakers, rape victims, martyrs, wet nurses, and more.

She is invoked during natural disasters like earthquakes, fires, and volcanoes.

She is often depicted in art carrying her breasts on a platter or holding the instruments of her own torture.

During the feast of St. Agatha in Italy, it is common to find breast-shaped pastries still.

In his painting of St. Agatha, painted around 1635-45, Francesco Furini depicts Agatha in soft sfumato, spotlit against a black background. She’s looking into the darkness. One of her breasts is showing. In her left hand, she holds the pincers used to remove her breasts. The internet tells me there’s a palm branch (the traditional symbol of martyrdom) in her right hand. I can’t see it because of that black background.

Her hair is tied up with pink ribbon.

This is the saint of the male gaze, someone so pious and yearning as to embrace her torture, to gaze longingly into, what? The men of the era would say God. One of the many reasons I say, You can take your God, I don’t want him.

There are, of course, many paintings from this perspective—many in which Agatha holds her severed breasts on a plate, tame compared to others like the one in the Church of Santa Maria Maggiore in Ravenna, where we see Saint Peter’s visit to a bare-chested Agatha—two red wounds where her breasts were severed. In this painting, Agatha is muscular and broad-shouldered, large hands and a thick neck. She is strong. Though I imagine this is medieval commentary on what a woman is without her breasts.

In another horrific painting from the fifteenth century on an altarpiece in the Vatican, one of Agatha’s severed breasts hangs by a cord from her left hand. In the Church of Saint Agatha in Rome, the very large painting of the passion of Saint Agatha is another bloody, shirtless scene.

Then there’s sixteenth century painting by Sebastiano del Piombo for a Cardinal’s “private worship collection” called “Martyrdom of St Agatha.” It is the strangest painting. Everyone in the painting, including Agatha, is calm and emotionless (not that abnormal for the times). There are six men, two of them Roman soldiers. All are looking at Agatha, who stands naked from the waist down. Two crouching guys have her breasts in these long pincers, but instead of any normal response, she’s both staring at and through this other guy who looks back at her menacingly while leaning in a leisurely gesture, as though he’s just a dude at the bar. Agatha’s face has this look of simultaneous agony, ecstasy, and disassociation while this dude watches like she’s the entertainment but also like he’s daring her to say or do anything to get herself out of the mess she’s in. Zoom in on the painting. This guy has me all sorts of twisted up.

As an atheist, anti-religion-but-privately-spiritual feminist type who grew up in “the church” and experienced first-hand what a “woman’s place” looks like, I like to read Agatha’s story not as it’s been painted, faux devotional—because we know exactly what that looks like—but as a self-protective refusal. A teenager refusing to sleep with a creep, even after a series of unspeakable tortures meant to make her, what, more inclined to want him?

She refused to relinquish control over her body. She wouldn’t cave, not when he sent her to the brothel, not when he had her tortured and maimed, not when she was dying in prison.

In fact, she refused in so many words when she told her torturers:

“Your words be but wind, your promises be but rain, and your menaces be as rivers that pass, and how well that all these things hurtle at the foundement of my courage, yet for that it shall not move.”

My Book Cover Is Beauty Revealed

I had it in my head for a long time that the Furini painting, the one where Agatha’s looking into the darkness, should be the cover of my book, Agatha. Seeing as how the foundational poems are poems in Agatha’s imagined voice.

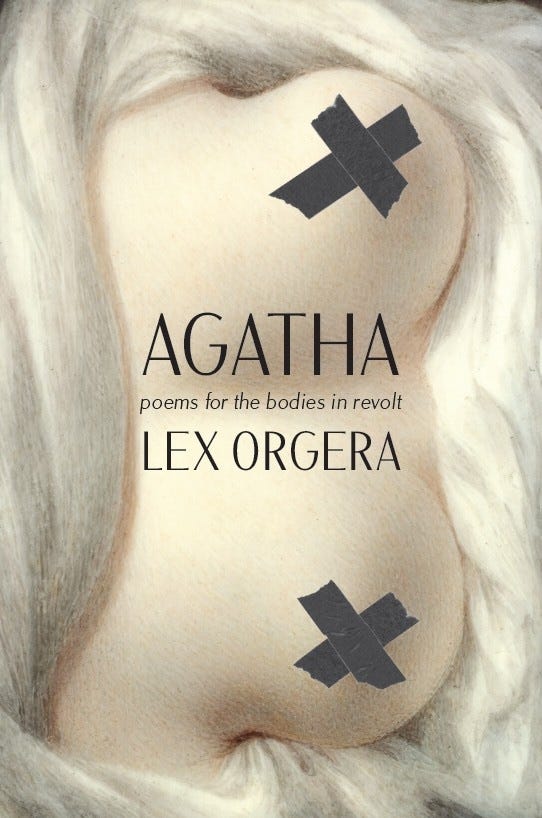

And my publisher and designer obliged with a version of the cover using that painting. But then the designer, thank heavens, presented this other thing, this unexpected option:

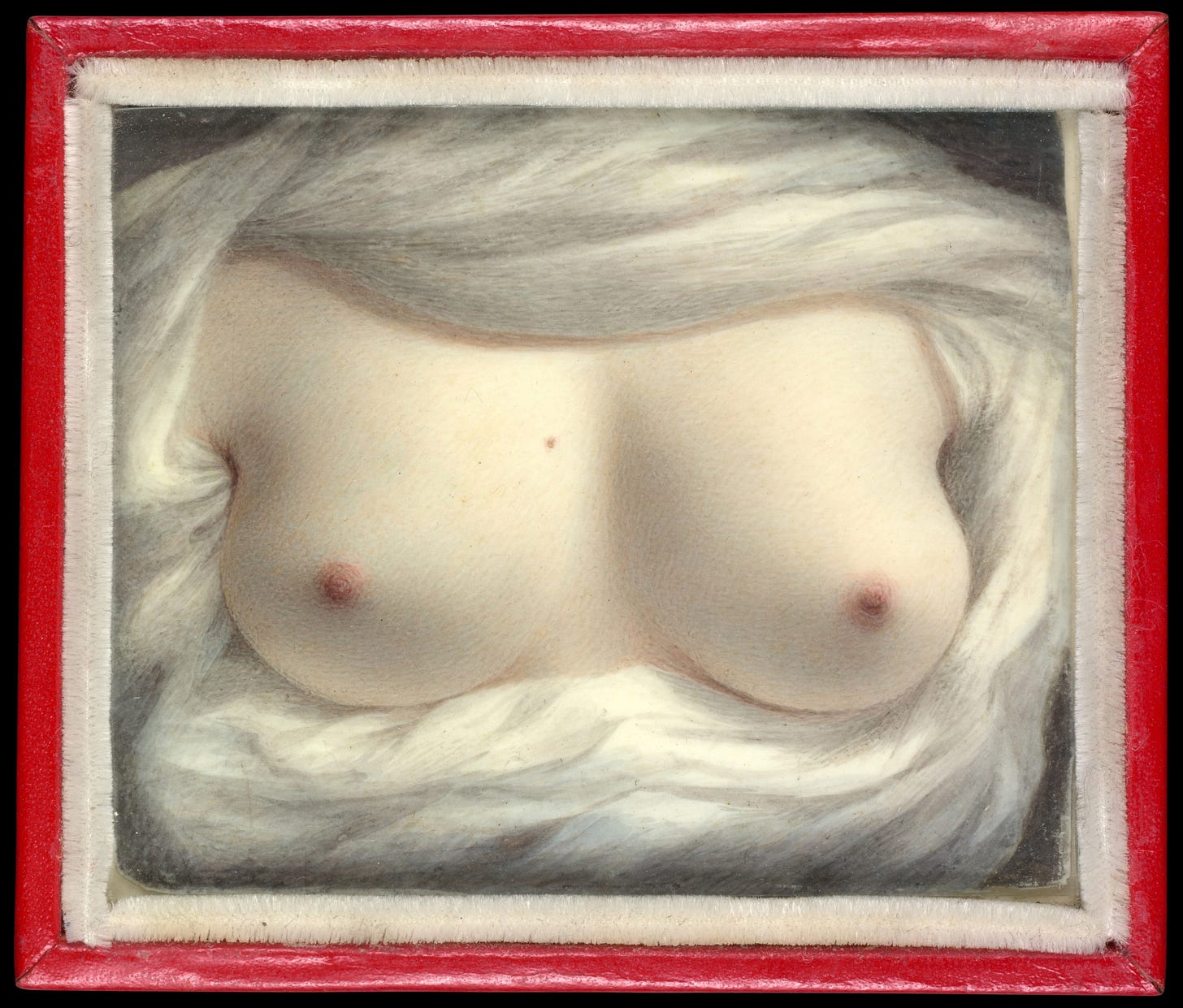

A painting of a pair of ivory breasts with two black X’s over the nipples (not part of the original painting). It was not even a contest. This, instead, would be my book cover.

The painting, “Beauty Revealed” is a 2.6-by-3.1-inch miniature in a red leather case that now lives in the Portrait Miniatures by American Women Artists room of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Watercolor on ivory, the 1828 painting is a self-portrait by Sarah Goodridge, a Boston miniaturist of some renown in her day. In fact, she was one of the first women in America to make a living from her art.

Goodridge painted her breasts in miniature, what one critic calls a “proto-sext,”1 for statesman Daniel Webster—almost assuredly her secret lover—who kept the image until his death and whose ancestors donated it to the Met. The painting is straightforward, literally, and that’s what I love about it. There’s nothing of how John Updike once described it: “Do we imagine a plea, a silent chastisement, emanating from these so vivid but ethereally disembodied breasts?” Oh, suck it, John. This is no coy invitation, no fluttering of eyelashes here, no downward gaze of objectification. No begging. No games. Nope, this painting reads, “Here I am. Enjoy.”

Goodridge painted in a tradition of miniatures that began in Europe as a way to keep one’s lover at hand. Sometimes miniatures were in the form of a lover’s eye. But, as far as I know, the breasts were a bold and unique move.2

I love what Dr. Chelsea Nichols says about Goodridge on her blog discussion about why Goodridge’s painting doesn’t necessarily mean she was trying to land a husband, either:3

“This is why I dislike the ‘honey trap’ theory of this painting. Goodridge strikes me as a remarkably independent woman for her time: one of the very first professional artists in New England at a time when there were very few self-supporting painters, let alone female ones. Marrying Webster to become a stuffy politician’s wife would have meant a considerable loss of independence, creative freedom and even financial security for her. And, judging by the self-portrait, Sarah and Daniel enjoyed an erotic and exciting relationship as lovers. Why give all that up?”

While he eventually married another woman—someone with a wealthy father—Goodridge had visited him in DC twice after his first wife died. Letters from him suggest that they often saw each other when he was in Massachusetts for much of the year—and not just when he was single. The two wrote letters for the next twenty odd years. Goodridge bequeathed him her paint box in her will.

She never married.

Other things I love about Sarah Goodridge’s story:

She bought a townhouse in Boston’s Beacon Hill, took care of her ailing mom, a paralyzed brother, and raised her orphan niece with the money she made from painting miniatures.

When she was a kid, because paper was expensive and hard to come by in the late 1700s, she drew with a pin on birch bark. And also with a stick on the kitchen floor strewn with stand.

She was largely self-taught.

Her dad was either an itinerant shoe salesman or a farmer-mechanic. Her mom was named Beulah.

One of her brothers was a famous organ builder. Some say this is how she met one of her great mentors, Gilbert Stuart, when her brother gifted him an organ.

She lost her eyesight at the end of her life. Well, I don’t love this part of the story. She was force to quit painting. She probably felt an acute and unbearable sense of loss.

But I digress. The breasts. This is why I love these particular breasts as the cover of Agatha. Because they were painted by her. This woman who walked outside the bounds her whole life and supported herself and made a painting that pushed some serious boundaries in the early nineteenth century. Majorly ahead of her time.

This Is Not What You’d Call a “Funny” Book

Though it is playful sometimes, with language. For instance, I have a poem in Agatha called “Agatha Muses on Her Torture,” and it’s not very, um, reverent. In fact, the poem was born out of a list I made during a long shift as a barista some thirty years ago: all the different names for boobs I, or my café compatriots, could think of, my favorite of all time being “dinners,” (South Carolina slang) with “jubblies,” (of Australian origin), a close second.

Listen. There are all sorts of serious, important discussions to be had around breasts, some of which I’ve had to have (the biopsies!); whether to have breasts at all; whether or not to reduce one’s breasts or enlarge one’s breasts; motherhood and breasts; sex and breasts; cancer and breasts; exploitation and breasts; men looking at your boobs instead of your face, etc. etc.

One story haunts me. I’ve told it to y’all before: My nonna’s old silicone implant, that she got post-mastectomy back in the eighties, grew to the size and hardness of a cantaloupe over the course of twenty years and migrated up toward her shoulder where it lived, hard and painful, for another twenty years. When she finally got the thing removed—she’d refused all those years at the advice of a doctor I wish I could strangle—she was 93. She never recovered from that surgery, and while it was maybe her only option, I kind of what to strangle that surgeon too. She lost the thread after that. As if she’d lost a friend or a lover. Her brain stopped working.

There is a crazy-making to this kind of powerlessness.

The cover of Agatha—a book I wrote over the course of a lot of years, one that explores my own ever-morphing experience of what it means to live in a body with breasts, and excavates revolution, goodness, and divinity—combines that powerful Goodridge self-portrait with big Xs—the X being (besides practical because, well, a breast’s nipples are scary?) Agatha’s autonomy, her choice-making, negated by some horny civil servant with just a little bit of power. Which is the age-old story. The story of ripping away a woman’s choice. But, look, it’s also the story of those women who refuse, who risk, who walk outside the lines, who make their own way.4

A Few Good Links

Pre-order Agatha here.

I made a new website! It’s not totally finished, but I think it looks pretty ok.

New poems from Arts & Letters: “The Smartest Mollusk” and “Mountain Time”

https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/sarah-goodridges-beauty-revealed-1828/#p-1-0

One thing that annoys me is how many critics talk about Goodridge being forty but her boobs looking much younger. Which is dumb on several levels. Let’s just get that straight.

https://ridiculouslyinteresting.com/2019/04/29/a-saucy-self-portrait-from-1828/

Preordered -- congrats!

love this cover and this post, looking fwd to it lex!